Maryam Ogunniyi, a student at Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, Nigeria, had a transformative experience when she accompanied her friend Nafisa Abubakar to a Diphtheria infection program organized by Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders). Nafisa, who was interning at a primary healthcare centre in Kano state, introduced Maryam to this previously unfamiliar illness.

During the programme, Maryam absorbed crucial information about Diphtheria. She now understands that it is a respiratory disease, transmitted through the air and highly contagious, particularly when in close proximity to an infected individual.

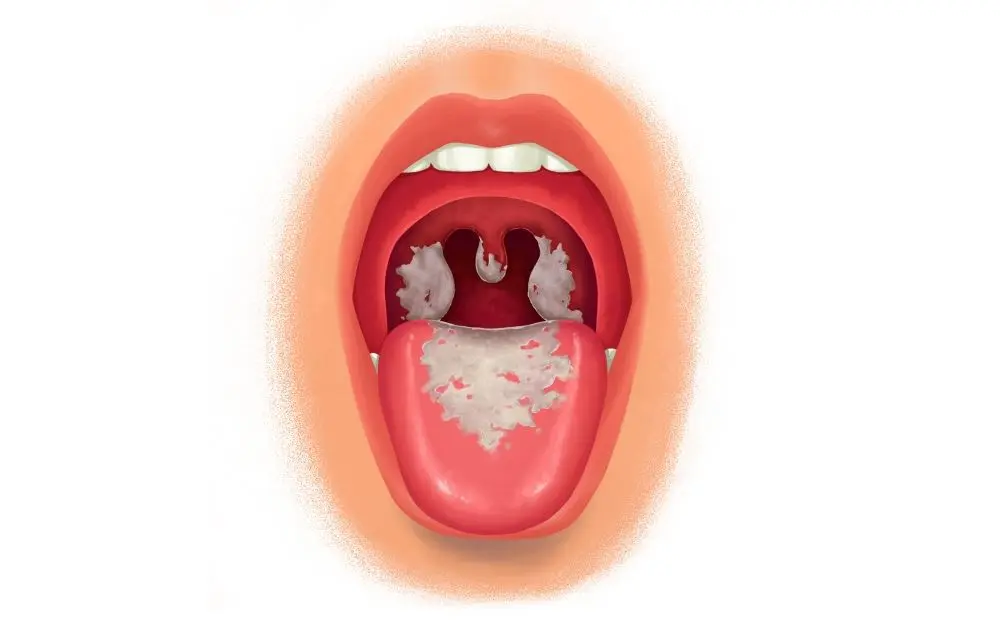

She says, Prevention measures, much like those for the coronavirus, include consistent use of face masks and diligent handwashing. Notably, one of the symptoms involves the development of wounds in the upper respiratory tract and mouth.

Referred to as “Agalawa” in the Hausa language, Diphtheria had become alarmingly prevalent in Kano at that time she added.

In the realm of infectious diseases, few strike fear into the hearts of medical professionals quite like diphtheria. This insidious ailment ravages the upper respiratory tract, inflaming the delicate mucous membranes that line our airways. Caused by the bacterium Corynebacterium and transmitted through personal contact, diphtheria is a highly infectious and potentially fatal condition, making it the most dreaded of all childhood diseases.

According to the Nigeria Centre for disease control, Nigeria recorded diphtheria outbreaks between February and November 2011 in the rural areas of Borno State, north-eastern Nigeria, where 98 cases were reported.

Dr. Salim Abdullahi, an expert in the field, explains that diphtheria spreads through the air, carried by tiny droplets that hang in the atmosphere. “It is an airborne infection,” he warns, highlighting the ease with which this silent assassin can infiltrate our lives.

The symptoms of diphtheria may not manifest until 2 to 4 days after exposure, and in some cases, it can take up to 2 weeks for signs of infection to appear. The severity of the symptoms depends on the affected area, with the upper respiratory tract being the primary target. The bacteria responsible for diphtheria produce toxins that attack the mucous membrane of the throat, leading to potentially devastating consequences. However, it is worth noting that diphtheria is a vaccine-preventable disease, offering a glimmer of hope in the face of this deadly foe.

Causes and Prevention: A Race Against Time

Dr. Omotosho Wasiu, a consultant ear, nose, and throat surgeon at the University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, emphasizes a crucial factor in the emergence of diphtheria: reduced vaccine coverage. He advocates for increased awareness campaigns, especially in rural communities, as well as improved access to healthcare facilities. Dr. Wasiu believes that enhancing living conditions, ensuring access to clean water, and promoting better sanitation practices will play a pivotal role in curbing the spread of the disease.

“Diphtheria is a life-threatening disease,” warns Dr. Wasiu, urging individuals to promptly seek vaccination to protect themselves from this deadly scourge and reduce the risk of infection.

Fortunately, treatments for diphtheria exist. Patients diagnosed with the disease are isolated to prevent further transmission, and immediate medical intervention is administered. In rare cases, diphtheria can affect unusual sites such as the ears, causing infections, or the eyes, leading to redness and discharge. It can even cause itching in the eyes. However, the most alarming complications arise when diphtheria spreads beyond the respiratory system, affecting vital organs such as the heart, kidneys, and brain. These potentially life-threatening developments underscore the severity of the disease.

Dr. Salim Abdullahi reveals that diphtheria was once alarmingly prevalent in Nigeria a decade ago, with thousands of reported cases. However, recent success in immunization efforts has contributed to a decline in the incidence of the disease. Nevertheless, diphtheria remains a threat that can affect individuals of all age groups, particularly those who are unvaccinated. While the disease can be managed, not all cases result in mortality. Supportive care, including oxygen therapy, antibiotics, isolation, secretion clearance, and good hygiene practices, can improve outcomes. Definitive treatment often involves administering antitoxins.

Global Epidemiology: A Silent Menace Resurfaces

According to the National Library of Medicine, a staggering 8,819 cases of diphtheria were reported worldwide in 2017, marking the highest incidence since 2004. Unfortunately, recent data on diphtheria epidemiology remain scarce, with underreporting suggested due to incomplete surveillance data from the World Health Organization (WHO).

The launch of the WHO’s Expanded Programme on Immunization in 1974, which recommended a three-dose series of the DTP vaccine for all infants by six months of age, was a significant milestone. However, the 1990s witnessed a resurgence of diphtheria in the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union, with 157,000 cases and 5,000 deaths recorded. This alarming outbreak served as a poignant reminder of the potential for severe diphtheria outbreaks in communities with large populations of non-immune adults and inadequate vaccination coverage for children.

Preventing Diphtheria: A Call to Action

Dr Salim Abdullahi emphasizes that the diphtheria vaccine is crucial to immunization schedules, particularly for densely populated areas, school children, and close contact with diphtheria cases. He advocates for increased awareness campaigns through government, media, and non-governmental organizations, including religious and ethnic leaders. To further bolster prevention efforts, legislation mandating diphtheria vaccination for parents is deemed essential.

A Grim History and the Promise of Progress

Historical records from the Dittrick Medical History Center of Case Western Reserve University trace the origins of diphtheria back to ancient Egypt and Greece. However, it was after 1700 that severe recurring outbreaks began to plague humanity. This dreaded disease claimed the lives of one in every ten infected children. Symptoms ranged from excruciating sore throats to suffocation caused by a peculiar “false membrane” that enveloped the larynx. Diphtheria primarily targeted children under the age of 5, and until the 1920s, it was viewed as a death sentence due to the lack of effective treatment options.

The advent of vaccination offered hope, transforming diphtheria from a looming menace to a rare threat. Previously, the only recourse for treatment involved the painful procedure of tracheotomy—cutting open the throat without anaesthesia and inserting a tube directly into the windpipe. This enabled attendants to maintain a lifeline of airflow to the lungs.

However, a tracheotomy was considered a last resort due to the risks of infection, lack of anaesthesia, and low success rates. Only in the 1960s did operative complications diminish, marking a turning point in the battle against this relentless adversary.

While diphtheria may no longer cast a constant shadow over children, the memory of its devastation and the ongoing efforts to combat it remind us that our fight against infectious diseases is an ever-evolving endeavour.

According to experts, the battle against diphtheria can be won through a combination of vaccination, increased awareness, and enhanced healthcare.